#28. Luffing all the way to the Bank: Trump Ocean Club, Panama (2011)

South of the border, down Panama way, Trump's Russian Laundromat switched its spin cycle to overdrive.

When the sail-shaped Trump Ocean Club first took its place in Panama City’s skyline, the building(later renamed the Trump International Hotel and Tower Panama and, still later, renamed again the JW Marriott Panama) was presented as the last word in international luxury. But by the time it opened in 2011 as the Trump Organization’s first overseas hotel, the cognoscenti realized it had become something entirely different. Instead of functioning as a glamorous oasis for the rich and powerful, it had become a high-speed laundromat that washed enormous amounts of tainted capital. At the heart of the operation was a sales team that expertly courted wealthy foreigners—many of whom were Russian or Soviet émigrés—and leveraged the Trump brand to command inflated prices and launder money.

Like most of the projects he started after his crippling bankruptcies in Atlantic City, the Panama tower was not built by or financed by Donald Trump. After all, most banks wouldn’t touch him. Moreover, Trump had become party to a scheme by which he licensed his name and provided management services so that he could shift all the risk that went along with financing and development to local partners while he benefitted from a lucrative payday. Better yet, the arrangement continued to generate millions in management fees and royalties for Trump that amounted to nearly $14 million, even though the project itself faltered and buyers were left exposed

As I wrote in House of Trump, House of Putin:

Trump fostered similar relationships all over the world. In 2003, Trump had whetted Latin American interest in the Trump brand by staging the Miss Universe pageant in Panama City, Panama. Three years later, he struck a deal in Panama to develop the Trump Ocean Club International Hotel and Tower, a sail-shaped seventy-story waterfront complex that included residential apartments and a casino. According to an investigation by Global Witness, an anticorruption watchdog, Trump was entitled to a licensing fee, 1 percent of any financing he secured, and a cut of every unit sold—all of which would add up to more than $75 million. Many of the problems behind the project led to a man named Alexandre Ventura Nogueira, the tower’s primary broker. According to a report by Reuters, Nogueira, who, with his partners, sold more than half the apartments in the project, marketed the condos largely to Russians because, a colleague said, “Russians like to show off. For them, Trump was the Bentley” of real estate brands.

According to conversations secretly recorded by a former business partner, in 2013 Ventura Nogueira said he had laundered tens of millions of dollars through real estate. “More important than the money from real estate was being able to launder the drug money—there were much larger amounts involved,” he said in the recording. “When I was in Panama I was regularly laundering money for more than a dozen companies.”

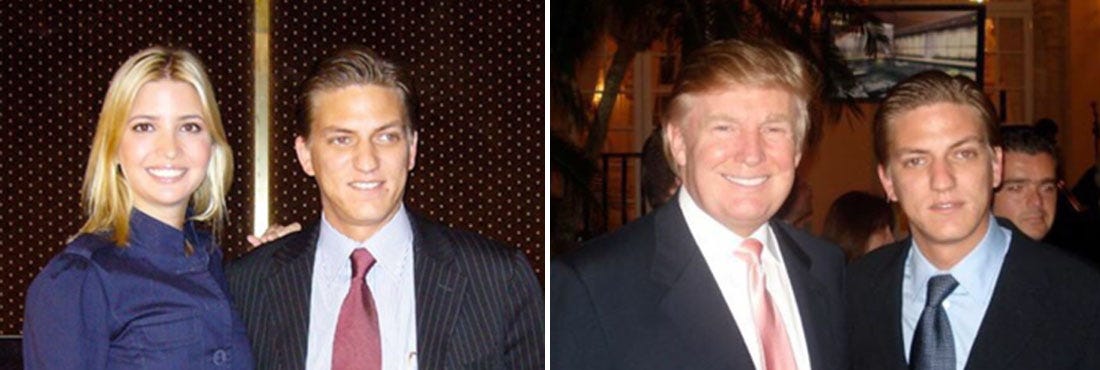

Nogueira told Reuters that he became the leading broker for the project thanks in part to the support of Trump’s daughter Ivanka, who appeared in a promotional video with him. The Trump Organization went into overdrive with the new model. Why not? Since Trump did none of the financing and almost none of the development, its risks were minimal and the upside was high. The Trump Organization’s role in the Panama project “was at all times limited to licensing its brand and providing management services,” said Alan Garten, the company’s chief legal officer. “As the company was not the owner or developer, it had no involvement in the sale of any units at the property . . . No one at the Trump Organization, including the Trump family, has any recollection of ever meeting or speaking with this individual [Nogueira].”

Garten’s assertions notwithstanding, Nogueira was at the center of sales for the project. A Brazilian who won his position after meetings with Ivanka Trump, Nogueira reportedly treated the project as “Ivanka’s baby,” and sold between 350 and 400 units. He even celebrated his success at Mar-a-Lago in 2007, where guests tied to the project mingled with the Trump family and where a promotional pitch boasted that the tower was selling “like hot cakes.”

Nogueira admitted on camera and on tape that “nobody ever asked” who his customers were or where their money came from, noting that neither banks, developers, nor the Trump side ever showed interest in the source of funds. In separate recorded conversations authenticated by people who knew him, he bragged about laundering “tens of millions of dollars” through contacts in Miami and the Bahamas, while still insisting he didn’t “knowingly” channel dirty money through the Trump Tower itself.

According to an investigation by Global Witness, among Nogueira’s customers and partners were alleged Colombian money launderer David Murcia Guzmán, who wired $1 million towards his condo purchases; early investor Louis Pargiolas, later convicted in a U.S. cocaine-import conspiracy; Belarus-born Alexander Altshoul and his relative Arkady Vodovozov, the latter of whom had been convicted by Israeli authorities of kidnapping and death threats; Canadian émigré Stanislau Kavalenka, who faced pimping and kidnapping charges that were later dropped; and Igor Anopolskiy, was eventually sentenced on charges of forgery and people smuggling in Ukraine.

The pipeline from Moscow and the post-Soviet space was cultivated deliberately. Trump’s partners made repeated trips to Russia, hired Russian-speaking brokers, and pitched the brand as a kind of luxury premium—“for them, Trump was the Bentley,” one participant recalled. The sales structure was designed for opacity: in 2006–2007 alone, at least 131 Panama holding companies with variations of “Trump” and “Ocean” in their names were registered to warehouse pre-sale agreements. Bearer shares, bulk contracts, and corporate shells made it nearly impossible to trace beneficial owners, while airport pickups in a white Cadillac emblazoned with a Trump logo offered arriving foreign investors a frictionless buying experience where documentation, not due diligence, was the priority.

Legal and compliance experts later said the red flags should have been unmistakable. According to the Reuters report, former Manhattan assistant District Attorney and JPMorgan anti-corruption head Arthur Middlemiss warned that any U.S. counterparty doing business in a high-risk jurisdiction like Panama risked “turning a blind eye” under U.S. law by failing to vet clients, while former Treasury enforcement undersecretary Jimmy Gurule emphasized that sound ethics alone should have barred working with people linked to criminality. Yet at the time, no laws required developers or brand licensors like Trump to conduct due diligence on unit purchasers. The Trump Organization has consistently maintained that its role was “limited” to branding and management, with no control over unit sales or broker retention, and, as always, had no recollection of substantive dealings with Nogueira.

Behind the glossy marketing lay the ugly reality of kleptocratic finance. Panama’s real estate market, described by prosecutors as filled with towers designed to “legalize your money,” provided the perfect venue for anonymous corporations to park illicit cash, flip contracts, and cycle proceeds into banks. The Trump Ocean Club became a magnet for organized crime, with Russians and other foreign buyers leading the way even though many of them never intended to live in their units. Journalist who visited the development found darkened apartments, empty restaurants and deserted hallways— a physical reminder that the building was less a residence than a money-laundering machine

So, ultimately, the Trump Ocean Club collapsed under its own weight. In 2009, Nogueira was arrested on unrelated charges of fraud and forgery, released on $1.4 million bail, and fled while facing multiple criminal cases. Investors later alleged that he had double- and triple-sold units, while the global financial crisis wiped out speculative demand. The developer, Newland, defaulted on its bond payments, leaving investors and bondholders to absorb losses after restructuring. Yet Trump still walked away with between $30 million and $50 million, according to court records from the 2013 bankruptcy, thanks to a licensing model that secured his revenue.

In a country long defined by corruption and money laundering, the deal was bound to unfold this way. Long a haven for money laundering, Panama sought to rehabilitate its image with global prestige projects such as hosting Miss Universe in 2003 and unveiling the Trump Ocean Club in 2011. Yet its former president, Ricardo Martinelli, was later arrested on an extradition request tied to corruption, and watchdogs repeatedly warned that without more transparency regarding beneficial owner and without serious screening regarding the source of funds, luxury real estate would remain a laundromat for drug cartels, mobbed-up intermediaries, and post-Soviet elites who needed a place to park their stolen gains.

The tower’s troubles did not end with its construction or even its bankruptcy. According to The Guardian, in 2018, the Trump Organization was forcibly ousted from management of the Panama property after a standoff with its new owners, who accused Trump’s team of mismanagement and obstructing the handover.

For all the mirrored glass and promises of luxury, the Trump Ocean Club was never really about condos but about moving money, more often than not, dirty money, and once again, Donald Trump just couldn’t get enough Mafia money. It was a pattern that he repeated throughout his career.

Cast of Characters

Donald Trump

Licensed his name to the Panama tower, stood to make over $70 million without investing a cent, and walked away with tens of millions even as investors and buyers lost out.

Ivanka Trump

Oversaw the project, promoted it as her “baby,” appeared in sales videos, and cultivated relationships with brokers like Nogueira.

Alexandre Ventura Nogueira

Brazilian salesman who sold up to half the units, later admitted to laundering money, fled Panama after fraud charges, and became the face of the scandal.

David Murcia Guzmán

Colombian narco-operator who wired $1 million to buy multiple units, later convicted in the U.S. for laundering cartel money.

Louis Pargiolas

Early investor, later pleaded guilty in Miami to conspiring to import cocaine.

Alexander Altshoul & Arkady Vodovozov

Belarusian-Canadian investor and his cousin; Vodovozov was convicted of kidnap and violent threats in Israel.

Igor Anopolskiy

A Ukrainian investor in the Panama development, Anopolskiy received a suspended sentence for people smuggling and forgery.

Stanislau Kavalenka

Belarusian-Canadian athlete turned investor, accused of pimping and kidnapping in Canada, charges later dropped when witnesses vanished.

If you have tips, leads, or insights, please reach out—I am always looking for new information. And don’t forget to comment and share your thoughts!

For the complete story on how Trump became a Russian asset, buy House of Trump, House of Putin, and/or American Kompromat. And don’t miss my latest book, Den of Spies!

House of Trump, House of Putin

The Untold Story of Donald Trump and the Russian Mafia

American Kompromat

How the KGB Cultivated Donald Trump, and Related Tales of Sex, Greed, Power, and Treachery

Den of Spies

Reagan, Carter, and the Secret History of the Treason That Stole the White House

I’ve been using the research in your books, to point out Trump’s transnational criminal syndicate for a long time. It’s great that you share some of that knowledge here.

Slainte and thanks as always!

Thank Craig 🙂 appreciate your insight keep SPEAKING TRUTH TO POWER