1985-1986 The KGB Sets Its Trap

The Story Behind Trump's First Visit to the USSR: "Trump Melted Immediately."

As I wrote in an earlier post (1980 Former Soviet Agent: How Trump Was Lured into the KGB’s Web), there are important unanswered questions about what happened after Semion Kislin, an alleged spotter agent for the KGB, first made contact with Trump in 1980. The real issue was whether Kislin’s overture to Trump—selling him 200 television sets for the Hyatt Grand Central Hotel from an electronics store with ties to the KGB—would lead to a more important relationship with the Soviet spy agency.

To answer that question, I reached out to Yuri Shvets, a former KGB major who trained alongside Vladimir Putin as a classmate the Red Banner Institute and served at Washington Station, in D.C., in the Eighties. Shvets, who left the KGB during the last days of the Soviet Union and had since become an American citizen, had a pretty good idea of what happened because he was familiar with the protocols that he shared with his colleagues in New York who, he said, were cultivating Trump.

Immediately after selling the TV sets to Trump, Shvets said, Kislin would have had to notify his handler about the transaction. That was standard procedure. Once Kislin’s handler was activated, the New York rezidentura, i.e., New York Station in the First Chief Directorate of the KGB, would get its opportunity to develop Trump as a new asset.

If they followed procedure properly, Shvets said, this was almost certainly the point at which Donald Trump’s name first entered KGB files. “I’m ninety-nine percent positive this is how they started their file on Trump,” he told me. “Kislin would have gone to his handler and said he had an interesting contact. ‘The guy is Donald Trump. He is young, ambitious, rich. He might have a future.’”

“So you accumulate about ten meaningful reports on the guy,” Shvets told me, “and you examine them to see if this guy can be cultivated to the point where he can be useful in either of two capacities. Capacity number one: as a trusted contact. Capacity number two, which is more ambitious: as an agent. You want to know if this guy can be cultivated to the point where he can be brought to cooperate.”

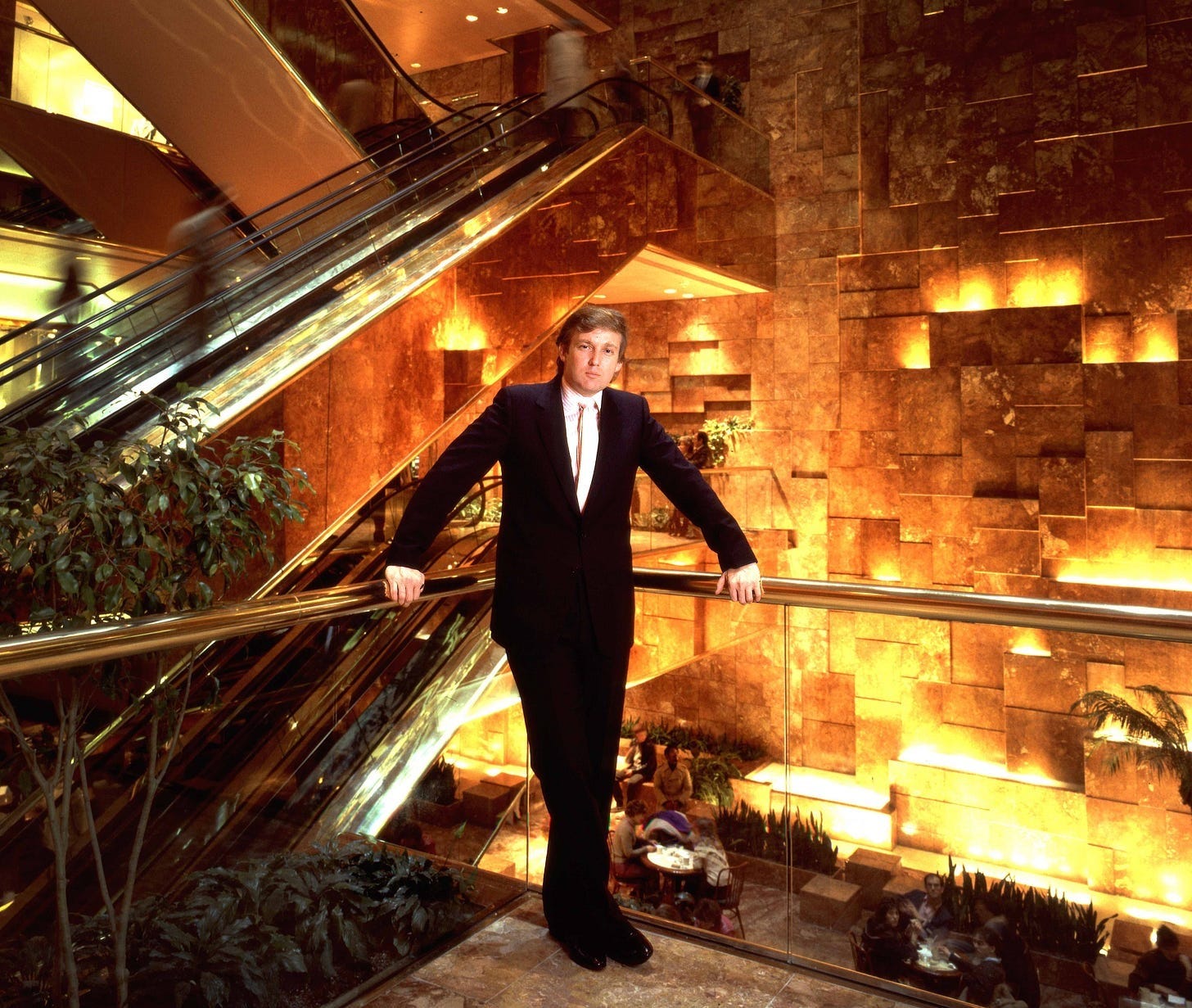

At the time, thanks to the success of Trump Tower in 1983, Donald Trump was well on his way to becoming a national figure–albeit one who provoked mixed reactions. New York Times architectural critics savaged the gaudy crown jewel of Trump’s real estate empire, as “monumentally undistinguished,” “preposterously lavish” and “showy, even pretentious.” But Trump, of course, loved it.

Trump was loud, vulgar, greedy, vain, and narcissistic. He was highly susceptible to flattery, money, and women. To the KGB, that meant he was perfect. He was exactly what they wanted.

“Trump was a dream for KGB officers looking to develop an asset,” Shvets told me when I interviewed him for American Kompromat. “Everybody has weaknesses. But with Trump, it wasn’t just weakness. Everything was excessive. His vanity, excessive. Narcissism, excessive. Greed, excessive. Ignorance, excessive.”

Old hands at the CIA agreed. “Trump is extremely vulnerable to flattery,” said Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, a former CIA station chief in Moscow. “He almost defines relationships entirely by who flatters him and who doesn’t, as opposed to the intrinsic value of what people say. He doesn’t care at all about the fact that Russians are masters at manipulation.”

Still, the KGB had no guarantees that developing Trump as an asset would pay off. Trump was just one of hundreds of assets they were cultivating. They could not have foreseen Trump’s political ascent. The KGB played the long game, but they did not seek him out as someone who could be groomed as a presidential candidate and activated decades later. Instead, in the Eighties, they cultivated hundreds of agents and assets in New York alone. It was like throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what would stick. Only time would tell if any such overtures would reap dividends.

There was no guarantee that developing Trump as an asset would pay off. The KGB played the long game, but they did not seek him out as someone who could be groomed as a presidential candidate several decades later.

Still, according to Shvets, Kislin’s bulk sale of television sets to Trump had been enough to trigger interest in cultivating him as an asset by the KGB. The next step in recruiting Trump was to bring him to the Soviet Union. By 1985, the idea of going to Moscow was not quite as daunting as it had been earlier in the Cold War. Thanks to the ascent of Mikhail Gorbachev as General Secretary, it seemed that the Russian bear had put on a friendly face. But Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) masked the fact that the KGB, under the guidance of General Vladimir Kryuchkov, a hard-liner who seemed to be swimming against the tides of history, was still the most effective and most feared intelligence-gathering organization in the world.

A compendium of memos entitled Comrade Kryuchkov’s Instructions: Top Secret Files on KGB Foreign Operations, 1975–1985, shows that by 1984 Kryuchkov was deeply concerned that the KGB had failed to recruit enough American agents and that absolutely nothing was more important. Consequently, he ordered his officers to cultivate as assets not just the usual leftist suspects, who might have ideological sympathies with the Soviets, but also various influential people such as prominent businessmen.

As a result, KGB headquarters sent heads of station a questionnaire itemizing the various qualities KGB assets should have. According to intelligence leaked by KGB defector Oleg Gordievsky, at the top of the list were high achievers in business and politics, particularly those whose profiles included corruption, vanity, narcissism, marital infidelity, and poor analytical skills.

And so, as if orchestrated by Kryuchkov, the political education of Donald Trump began in March 1986, when Trump met the Soviet Union’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Yuri Dubinin, and his daughter, Natalia Dubinina.

There are several accounts about what transpired, one of which comes from Natalia Dubinina herself, who, at the time in question, was part of the Soviet delegation to the United Nations. On November 9, 2016, the day after Trump won his first term, Natalia gave an interview to the Russian daily Moskovsky Komsomolets and said that when her father arrived in New York City for his very first visit, she met him at the airport and took him on a tour. One of the first buildings they saw was Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue. Natalia said her father told her he “never saw anything like [Trump Tower], that he was so impressed that he decided he had to meet the building’s owner at once.”

Then, according to Dubinina, they stopped, got out of the car, went into Trump Tower, and took the elevator right up to Donald Trump’s office.

But there are problems with Dubinina’s account. For one thing, if her story was true, she and her father would have violated every protocol in the books for the Soviet Union during that period of the Cold War.

For one thing, as Shvets explained, the arrival in the United States of a new Soviet diplomat, especially one who had never before visited America, was a big deal. The normal procedure would have been for Dubinin to be met at the airport by a delegation of Soviet officials and immediately taken to his office.

Moreover, at the time, all Soviet diplomats, except for intelligence officers, avoided all unauthorized, unofficial contacts with Americans. The same rules applied to both the Washington rezidentura where Shvets worked and in New York where Dubinina worked. At the time, virtually any Soviet citizen in the U.S. was considered a ripe target for the FBI. As a result, making unauthorized outside contacts with Americans was a fairly certain way to get in trouble with the KGB and win a one-way ticket back to the motherland. “It was a must. This was not a joke,” Shvets said. “Actually, it was explained politely to the ambassadors, that we care about your security, because, you know, CIA, the FBI, they're bad guys. They can kidnap you. They can drug you and, under drugs, you may tell state secrets, and then you'll be prosecuted. This is the reason why we need to protect you.”

KGB agents, however, were in a different category because it was their job to make contacts with and recruit Americans. After all, how could they possibly cultivate spies unless they were out and about? But according to Shvets, career Soviet diplomats who were not spies—the KGB referred to them as “clean”—rarely left their offices unless it was for a hearing on Capitol Hill, a public presentation of some report, or a run to the State Department to pick up official documents. So it was fairly easy to tell who among Soviet diplomats and journalists actually worked for the KGB.

“When my father told Trump that the first thing he saw in New York was Trump Tower, Trump immediately melted….He needs recognition and, of course, he likes it when he gets it. My father’s visit had an effect on him like honey on a bee.”

Natalia’s assertion that she and her father blithely ignored such strictly enforced protocols is not the only problem with her account. At the heart of her story is a simple but false assertion she made to MK: “My father was fluent in English.”

Far from being fluent, Yuri Dubinin was famous for not being able to speak English. In fact, his failure to learn the language was legendary. It was cited in the Washington Post, the New York Times, United Press International, the Chicago Tribune, Newsweek, and many other publications as being a highly unusual deficit for an ambassador in such a visible position.

In May 1986, just two months after moving to New York as ambassador to the United Nations, Dubinin was given an even more prestigious post as Soviet ambassador to the United States. As The Washington Post put it, Dubinin’s selection was “a surprise” because “Moscow broke with its practice of appointing experts on American affairs and fluent English speakers to its top diplomatic job in Washington.” Similarly, the New York Times noted that Dubinin’s appointment as the ambassador “startled some diplomats,” given that he had the “handicap” of needing “an interpreter in conversing with English speakers here.”

According to Newsweek, it was only after he arrived in the United States—that is, after he and Natalia met with Trump—that Dubinin began to study English with a tutor. Even then he needed interpreters to help him take questions in English at press conferences.

Shvets, who worked regularly with Dubinin’s KGB colleagues in New York saw it play out first hand. He even knew the tutor who was brought in by the embassy to attempt the hopeless task of teaching him English. “Because Ambassador Dubinin didn’t speak English, he just sat in his cubicle at the embassy without even leaving the premises of the building,” Yuri told me. “He was occupying the third floor, and he lived in complete seclusion. He was living as a hermit in the Soviet embassy. For at least a year and a half, after becoming the ambassador, he didn’t sign any cable coming from the United States to Moscow. Because he said, ‘Look, I don’t speak English. I don’t understand what they’re talking about on TV, what they write in the newspapers.’”

Yet another reason to question Dubinina’s account is Dubinina herself. In the late Seventies and early Eighties, Shvets told me, the position in the United Nations Dag Hammerskjöld Library allocated to the Soviet Union was held by Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Yelagin of the First Department (North America) of the KGB First Chief Directorate. When Yelagin returned to Moscow in 1982, Shvets, who worked with Yelagin for two years, says, he produced a paper titled “Using the UN Library for Collection of Intelligence Information.”

Translation: The UN harbored a nest of Soviet spies.

Nor was American intelligence in the dark about it. All in all, the mid-Eighties was an extraordinary period for the spy game. In January 1984, five Soviet spies were uncovered in Norway and expelled. In February, Soviet diplomat Viktor M. Lesiovsky died at the age of sixty-three–after telling the BBC that Soviet intelligence had achieved a “very substantial” penetration of the UN Secretariat. Later that year, Soviet spies were expelled or outed in Ethiopia, Denmark, and the U.S.

The next year, 1985, became known as The Year of the Spy and was filled with enough espionage to keep John Le Carré busy for decades, including the arrest of the John A. Walker family spy ring, and the hunt for moles that led to the eventual unmasking of the most damaging spies in American history — FBI agent Robert Hansen and the CIA’s Aldrich Ames.

In March 1986, the US demanded that the Soviet Mission cut personnel because of concerns they were spying. According to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the Soviet Mission had been widely infiltrated by the KGB, which led to the expulsion of twenty-five diplomats attached to the Soviet Mission to the UN later in 1986 and a total of more than one hundred by March 1988.

It is also suggestive that Natalia had graduated from Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), the prestigious Soviet foreign policy university that often served as a training ground for spies. Moreover, when one studied Dubinina’s CV, approximately two years of her life after graduation was shrouded in mystery. That was often the case, Shvets said, for young intelligence officers who train at the Yuri Andropov Red Banner Institute (the same spy school that trained Shvets and Vladimir Putin) and need to cover up those years with fictitious employment before they engage in operational work for the KGB.

Moreover, Shvets also noted that Dubinina held Yelagin’s job from 1985 to 1986, an assertion that is corroborated by an April 28, 2003, profile of her on the Russian website AIF Express. All of which strongly suggests, as Shvets points out, that Dubinina, far from being an innocent librarian, was actually working for the KGB.

And since her father didn’t speak English, that leaves Natalia as the likely KGB operative who made the initial contact with Trump during this period.

Finally, if Shvets’ analysis is right and Dubinina was one of the first KGB operatives to reach out to Trump, why on earth was she giving an interview in Moskovsky Komsomolets just hours after he had been elected president? “I know firsthand that Moskovsky Komsomolets was used for active measures by the Russian intelligence community,” Shvets wrote me in a text message. “I know their modus operandi, because I was trained by the same textbooks as Putin and those who are running Russian intelligence services. The content [in the Dubinina interview] was highly sensitive. It was not something the editor could print without authorization from the Kremlin.”

According to The Guardian, MK has aided both Soviet and Russian intelligence in the past in active measures, including publishing disinformation suggesting that Alexander Litvinenko, the renegade anti-Putin FSB agent who died of polonium poisoning in London, may have been killed by Americans.

“Dubinina had kept silent from 1986 until the day after Trump’s election,” said Shvets. “And suddenly she comes out with a big interview published the very same day. Her interview with MK was an important part of a major Russian HUMINT cover-up operation designed to camouflage the roots of DT’s contacts with the Russians.”

The significance of the Dubinina interview, Shvets added, was that it was the “origin story” regarding Trump’s ties to Russia. “Natalia was trying to show that it was her father [who initiated contact with Trump]—not her—and the contact was official and had nothing to do with Soviet intelligence." That was purpose number one. And number two, the KGB believed that Trump would read this article, or a translation of the article. It was like a reminder saying, ‘Guys, we remember. And you see, we are lying. . . . We are camouflaging our relationship, but we remember everything.’”

Shvets added, “The KGB modus operandi clearly shows that Natalia was a KGB officer, and her story in MK, together with some other Russian media publications, indicates that her interview was an attempt to cover up the true nature of the KGB contact with Trump.”

Dubinina has not responded to multiple attempts to reach her by the author by phone and email.

Trump, of course, saw things differently. These contacts from the Soviets were nothing more than a tribute to his dazzling accomplishments. According to Trump’s The Art of the Deal, at a 1986 luncheon given by cosmetics magnate Leonard Lauder, he happened to be seated next to Yuri Dubinin.

Trump later rhapsodized about the conversation in his ghost-written bestseller. “[O]ne thing led to another,” he wrote, “and now I’m talking about building a large luxury hotel across the street from the Kremlin, in partnership with the Soviet government.”

But Trump’s susceptibility to flattery seems to have blinded him to the reality that a Communist superpower didn’t want to build a monument to conspicuous consumption in Red Square.

“It was all bullshit,” said Shvets, “because the chances for his Trump Tower in Moscow were zero. But this is how they put people on the hook and say, ‘Look, I’d like you to come over and just discuss this thing with you.’ And this silly guy, he couldn’t understand what’s going on in Russia or in the Soviet Union in Moscow. Yes, he is flattered. He is happy. He sees beautiful women. He is like a peacock.”

And that, according to Shvets, is the story of how Donald Trump was invited to Russia.

Finally, as I wrote in American Kompromat, Shvets says the letter inviting Trump was written at the behest of General Ivan Gromakov in the First Chief Directorate’s rezidentura in Washington. Gromakov, who died in 2009, was a high-level operative who headed the Fourth Department of the KGB’s First Chief Directorate:

“It was an established procedure for the KGB stations in the US to use Ambassador Dubinin to pass on invitations to Americans to visit Moscow,” said Shvets. “Usually, those trips were used for ‘deep development,’ recruitment, or for a meeting with the KGB handlers. In most cases the trips were organized by Goscomintourist, the Soviet government traveler agency that was better known as Intourist and served as a front for the KGB. If the trip included all expenses paid by Intourist, it was a clear indication that the KGB was behind it.”

Trump was thrilled with the invitation, but there is no evidence that he was aware of General Gromakov’s role or the widely known fact that Intourist was a KGB front that allowed the Soviets to arrange travel and surveil virtually any foreigner who entered the Soviet Union.

Update! Several days after this article was posted, Dubinina responded to the author by citing a letter she wrote to French newspaper Le Figaro that addressed some of the questions posed in an article that cited my books:

I have never met Mr. Trump, nor participated directly or indirectly in the preparation of his first trip to Moscow.

I have never worked for the KGB.

I served as an international civil servant at the UN in the Secretariat's Documents Department in New York from 1984 to 1986 and therefore never represented the USSR in the United Nations.

It is worth noting that her response contradicts the account she gave to Moskovsky Komsomolets in 2016 in which she describes meeting Trump and how she was present at a meeting in which her father flattered Trump “like honey on a bee.”

Cast of Characters

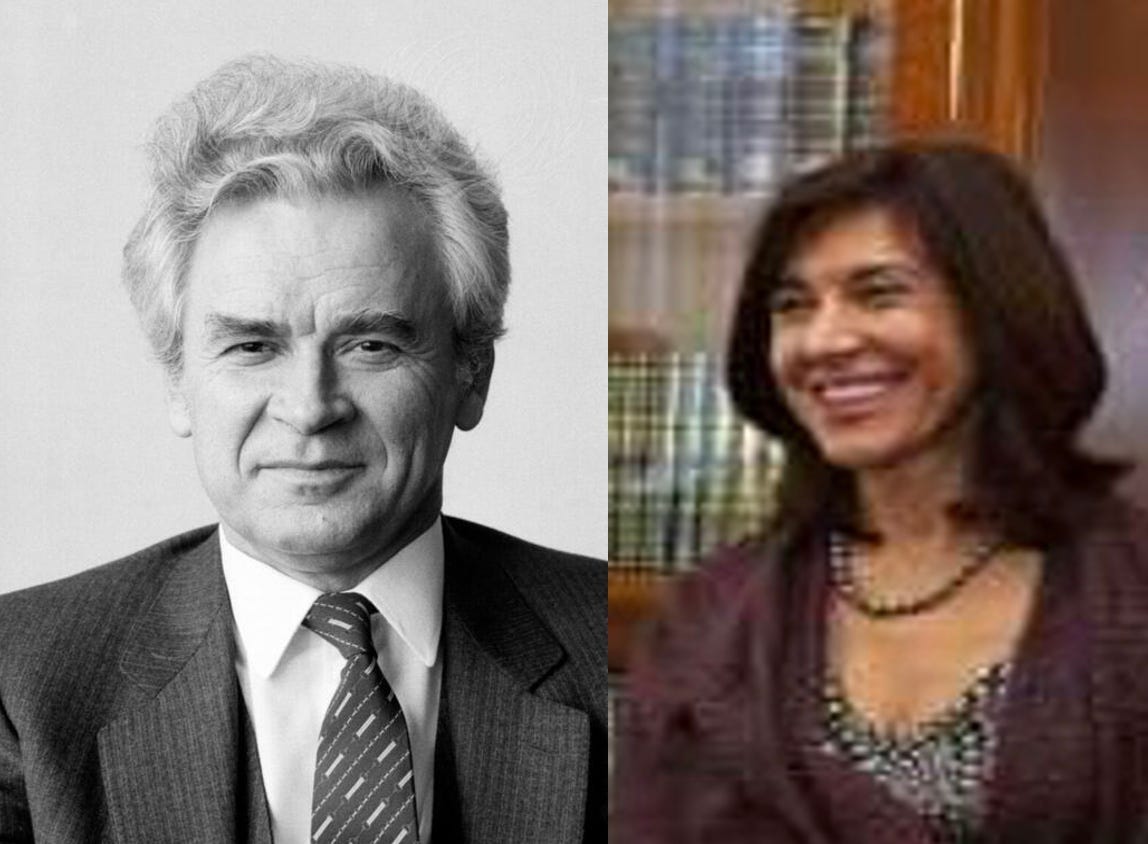

Yuri Dubinin

Soviet Ambassador to the United States (1986–1990) and previously the USSR’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations (1985–1986). Though he didn’t speak English, Dubinin invited Trump to the Soviet Union after a 1986 luncheon with him, and was allegedly used by the KGB to facilitate Trump’s visit as part of a cultivation effort.

Natalia Dubinina

Dubinin’s daughter and a UN “librarian” educated at MGIMO, the Soviet elite training ground for diplomats and spies. Likely a KGB officer, she reportedly made contact with Trump in 1986. According to Shvets, her 2016 interview was part of a Russian intelligence active measure to cover up the true nature of that contact.

Yuri Shvets

Former KGB major based in Washington, D.C. in the 1980s. Now a U.S. citizen, Shvets has provided key insights into Soviet asset recruitment. He identified Trump as having been cultivated as a “special unofficial contact” by the KGB—a status given to high-value individuals.

General Vladimir Kryuchkov

KGB hardliner and chief of the First Chief Directorate. In 1984, he ordered the aggressive recruitment of Western influential figures, including businessmen—particularly those with vanity, greed, and narcissism—fitting Trump’s profile perfectly.

General Ivan Gromakov

Senior KGB official who, according to Yuri Shvets, authorized the invitation to Trump through Ambassador Dubinin. The visit was arranged through Intourist, the Soviet state travel agency widely known as a KGB front used to arrange travel, surveil, and cultivate foreign visitors.

Stay tuned for more updates!

If you have tips, leads, or insights, please reach out—I am always looking for new information. And don’t forget to comment and share your thoughts!

House of Trump, House of Putin

The Untold Story of Donald Trump and the Russian Mafia

American Kompromat

How the KGB Cultivated Donald Trump, and Related Tales of Sex, Greed, Power, and Treachery

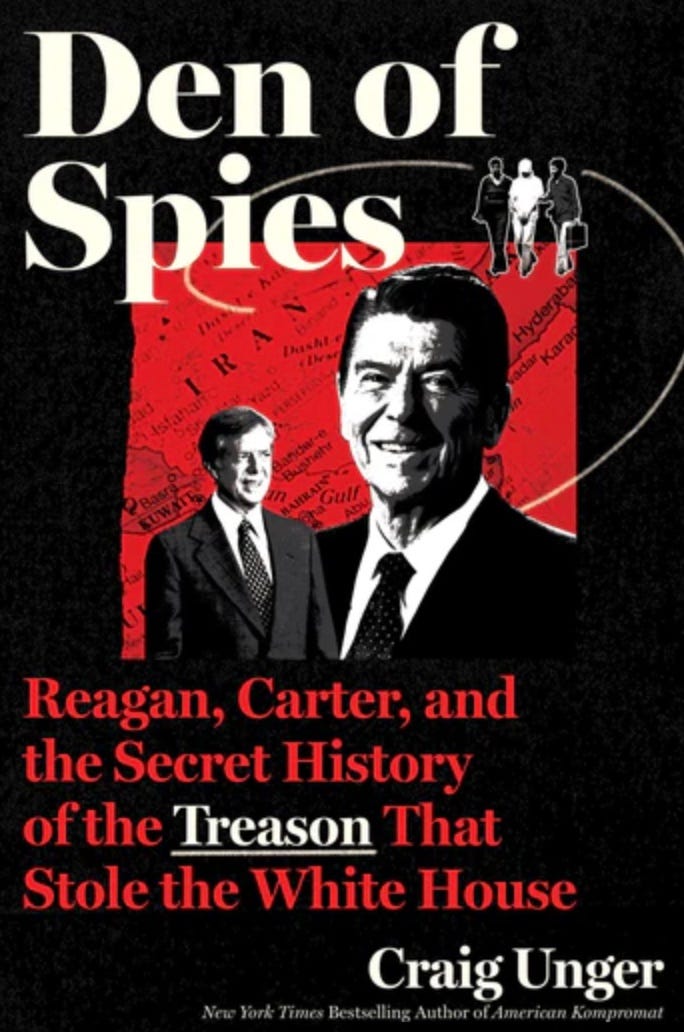

Den of Spies

Reagan, Carter, and the Secret History of the Treason That Stole the White House

This Craig Unger guy is on target. I do personally think Roy Cohn was his groomer and positioned to get t into the game. Real estate red lining slum lord? Kompromat from day 1. In my humble opinion.

Great work! 💪