#32. Missteps on the Steppes of Central Asia (2012)

After franchising his name in Azerbaijan and Georgia for projects that flopped, Trump continued to ransack the other remnants of the former Soviet Union. Next stop: Kazakhstan.

In 2012, Donald Trump was not yet ready to pursue the presidency, but he continued to cultivate relationships with oligarchs and autocrats in Central Asia who ruled over the remnants of the Soviet empire.

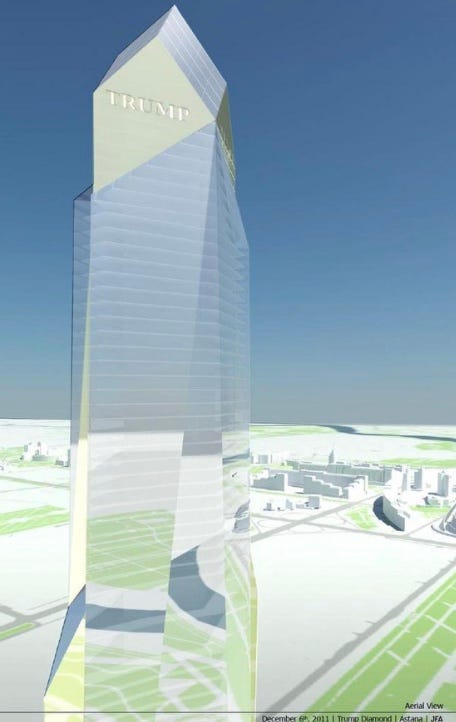

That year, in fact, the Trump Organization signed a letter of intent to license the Trump name to a luxury real estate development near the presidential palace of Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s in Astana. As a McClatchy investigation noted, the project, called Trump Diamond, was never built, but the attempt to develop it underscored how Trump’s organization operated—through alliances with authoritarian thugs, fueled by opaque capital, and protected by layers of secrecy that shielded corruption from scrutiny.

As we have seen, with the help of Felix Sater and the Bayrock Group, Trump had already been franchising his name to brand luxury high-rise projects in SoHo, Toronto, Panama, Georgia and more that were largely lucrative failures. Now, Trump partnered with another outfit, the Silk Road Group, the same company that was behind his failed venture in Batumi, Georgia.

This time, Trump’s target market was Kazakhstan, which just happened to be newly awash in oil money. Its capital, Astana—since renamed Nur-Sultan—had become a playground for Nazarbayev’s vision of absolute power. Financed via an intricate web of state contracts, kickbacks, and offshore accounts, it was a shimmering city built in glass and gold as if to reflect his personality cult. Enter, Donald Trump, who planned to have his name atop its most striking glass tower.

Behind the illusion of modernization was a regime built on graft. Nazarbayev’s relatives controlled the banks and energy firms. His cronies controlled the construction companies and transport networks. Vast fortunes siphoned from the nation’s oil and mineral reserves were quietly parked in London real estate, Swiss trusts, and Caribbean shell companies. Western developers and consultants, eager to profit from the boom, rarely asked where the money came from—or who was really paying.

For Trump, whose company was still staggering from the 2008 financial crisis, Kazakhstan offered another desperately needed lifeline. Trump’s post-recession strategy was to continue selling his name to anyone with cash and power—just as he had with Bayrock. Markets like Kazakhstan—operating in an unregulated, Wild West-like environment, and desperate for Western validation—were ideal.

In Trump Diamond, the future president saw all the benefits he sought with none of the risk: licensing fees, management contracts, and global publicity without a single dollar of investment. In exchange, Nazarbayev’s inner circle would be able to market one of the most recognizable brands in the world, a Western symbol that could buy them legitimacy and launder money at the same time.

According to contemporaneous reports, the 2012 letter of intent envisioned a gleaming skyscraper complex near the Ak Orda Presidential Palace, a tower meant to proclaim Kazakhstan’s arrival on the global stage. Trump’s role was purely symbolic. His company would provide branding and “consulting,” while local partners, deeply embedded in the political and financial machinery of Nazarbayev’s regime, handled financing and construction. Many of those partners had long histories of corruption and close ties to Russian oligarchs. They operated within the same ecosystem that bound Kazakhstan’s kleptocracy to the Kremlin’s economic interests: a world where revenue from oil sales, state contracts, and organized crime flowed together through offshore vehicles stretching from Cyprus to Switzerland to the British Virgin Islands.

Trump’s coziness with shady, criminal figures was nothing new. Since the 1970s, he had surrounded himself with mob-connected contractors, fixers, and financiers—legitimate or otherwise. After the 2008 crash, the Trump Organization became dependent on branding deals in countries where the rule of law could be bought and where the illusion of Western legitimacy carried enormous value. In Baku, Azerbaijan; in Panama City, Panama; and now in Astana, Kazakhstan, the Trump brand served as validation for businessmen who were, in reality, conduits for dirty money. The pattern never changed: minimal exposure for Trump, maximum access for his partners, and no questions asked about where their dirty money came from.

Among the other businessmen who backed major Astana developments was Kenes Rakishev, a Kazakh oligarch whose fortune and influence depended on Nazarbayev’s patronage and on his ties to Moscow’s security networks. Rakishev maintained close ties to senior Russian officials and to figures associated with the FSB (Russia’s security services), including allies of Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov. Many of his ventures overlapped with Kremlin-controlled enterprises and showed how deeply intertwined Kazakhstan’s business elite was with the Kremlin and Russia’s intelligence-linked circles—and how easily Trump’s brand became part of that same system.

Nazarbayev’s Kazakhstan was a textbook kleptocracy. The country was formally independent but politically and economically dependent on Russia. Its image of stability masked a system built on corruption, where Nazarbayev’s relatives and loyalists controlled major industries and operated like an organized crime syndicate. Government, business, and the criminal underworld were part of the same power structure. Trump’s business model fit easily into this environment, where political connections and private profit were traded interchangeably. He didn’t need to understand the details of Kazakhstan’s corruption to profit from it—he only needed to sign the deal and wait for the money to arrive.

During the Trump Diamond negotiations, Michael Cohen also worked with Giorgi Rtskhiladze, a Georgian-American businessman with the Silk Road Group, to explore financing for the project in Kazakhstan as he had previously done in Georgia. Cohen, then serving as Trump’s personal attorney and fixer, acted as the go-between, connecting the Trump Organization to prospective partners across the region. As I wrote in my previous article, Giorgi Rtskhiladze later resurfaced during the 2016 election, texting Michael Cohen about rumored “tapes from Russia” linked to Trump’s business partners at the Crocus Group.

Crocus—and the networks behind it—were already central to Trump’s next move. By 2013, his focus had shifted to Russia. That November, the Miss Universe pageant brought him into partnership with Aras Agalarov, who, as the Kremlin’s favored developer and head of the Crocus Group, maintained close ties to Nazarbayev’s inner circle in Kazakhstan at the same time that he was building luxury projects for the Russian state.

Consequently, the same nexus of oligarchs, fixers, and Kremlin-linked financiers that had surfaced in Baku and Astana now gathered around Moscow. From Azerbaijan to Georgia to Kazakhstan, the pattern never changed: Trump supplied his brand, and in return gained entry into networks saturated with laundered money and political influence. These relationships formed a financial ecosystem that Russia’s intelligence services already understood intimately. They didn’t need to invent kompromat; Trump’s record of risky partnerships, opaque finances, and moral bankruptcy had already provided them with all the leverage they could ever need.

Kazakhstan’s role in this transnational network has often been overlooked, but it was central to the movement of Russian and Central Asian money into the West. Its energy and banking sectors functioned as key channels for oligarchic wealth, moving billions through European shell companies and real estate portfolios. Nazarbayev’s regime maintained a careful balance in which it was loyal to Moscow while it was eager for Western validation. Consequently, it positioned itself as a bridge between the Kremlin’s political ambitions and the global financial system. Many independent investigations and policy reports have since detailed how money from across the former Soviet bloc—including Kazakhstan—moved into Western economies through real estate and shell companies designed to hide their true owners. Trump’s ventures fit neatly into that same pattern, turning his developments into entry points for corrupt money and status symbols for the oligarchs and power brokers who moved it.

As with many Trump Organization projects, the Trump Diamond in Astana was never even built, but the deal revealed a deeper truth about how Trump’s business functioned.

By the time Trump launched his presidential campaign in 2015, he had spent years embedded in a circuit of post-Soviet capital that blurred the lines between business, politics, and crime. And, when he entered the White House, those relationships continued and gave the Kremlin the keys to the vulnerabilities through they could manipulate Trump.

In the end, the failed project showed how easily Trump’s brand could be sold to corrupt regimes hungry for legitimacy. Within months, his pursuit of oligarch money would carry him to Moscow—into the orbit of Aras Agalarov, the Kremlin’s favored developer, and into a partnership that would bring him closer than ever to Putin’s inner circle.

Cast of Characters

Nursultan Nazarbayev

Dictatorial President of Kazakhstan who ruled his country from 1991 to 2019, Nazarbayev governed through patronage, repression, and a sprawling system of corruption that enriched his family and loyalists who controlled the nation’s banks, energy firms, and construction.

Kenes Rakishev

Kazakh oligarch with close ties to Nazarbayev’s regime and to Russian security-linked networks. Rakishev maintained relationships with figures associated with the FSB and Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov. His business ventures overlapped with Kremlin-connected enterprises and later surfaced in leaked communications tied to Russian influence operations.

Giorgi Rtskhiladze

Silk Road Group partner and deal-maker with U.S.–Eurasia networks; later surfaced in 2016 texts to Michael Cohen about rumored “tapes,” illustrating how Batumi-era intermediaries re-entered Trump’s political orbit.

For the complete story on how Trump became a Russian asset, buy House of Trump, House of Putin, and/or American Kompromat. And don’t miss my latest book, Den of Spies!

House of Trump, House of Putin

The Untold Story of Donald Trump and the Russian Mafia

American Kompromat

How the KGB Cultivated Donald Trump, and Related Tales of Sex, Greed, Power, and Treachery

Den of Spies

Reagan, Carter, and the Secret History of the Treason That Stole the White House

Great piece. It's remarkable how many shady projects over the years have had Donald Trump's name all over them.